ITINERARIES OF ESCAPE

25 November 2023

Ruby Brown, Longing, 2019, acrylic composite gap filler on canvas.

A one-day exhibition about domestic space, ritual, and coping strategies for precarious times.

Anita Cummins, Ellen Yeong Gyeong Son, Gemma Watson, Maggie Hensel-Brown, Renae Coles, Ruby Brown, Ruth Cummins, and Sophie Cassar. Curated by Anna Dunnill.

DIGITAL EXHIBITION CATALOGUE with texts by Anna Dunnill & Ellen Yeong Gyeong Son.

ITINERARIES OF ESCAPE: AN ESSAY

Anna Dunnill

In a child’s drawing of a house the door is a mouth. The two windows are eyes, open or veiled. “The house, even more than the landscape, is a ‘psychic state’,” writes Gaston Bachelard. (1) The house is an extension of your body.

~

In November 2020, Ruth posts a photograph on instagram. She’s made a quilt made out of her old shirts and jeans. For ten weeks from early August to mid-October we were tethered to our homes by an invisible string, five kilometres long. Within that circular space Ruth collected rocks on her daily walks, and filled the quilt with them. The quilt is called Weighted Blanket. It weighs 17 kilograms.

A weighted blanket works by reinforcing a sense of the body’s edges. The body – fragmented, soluble, porous – is given definition through the sensation of pressure, as liquid is defined by the shape of a glass. It is made solid and habitable.

In the photograph Ruth is lying in bed, underneath the quilt, only her face showing.

I imagine her walking the same path every day, as I did in lockdown, feet trudging the pavement in a familiar loop. Filling her bag and pockets with a few stones at a time until she had accumulated a pile big enough to cover her body.

~

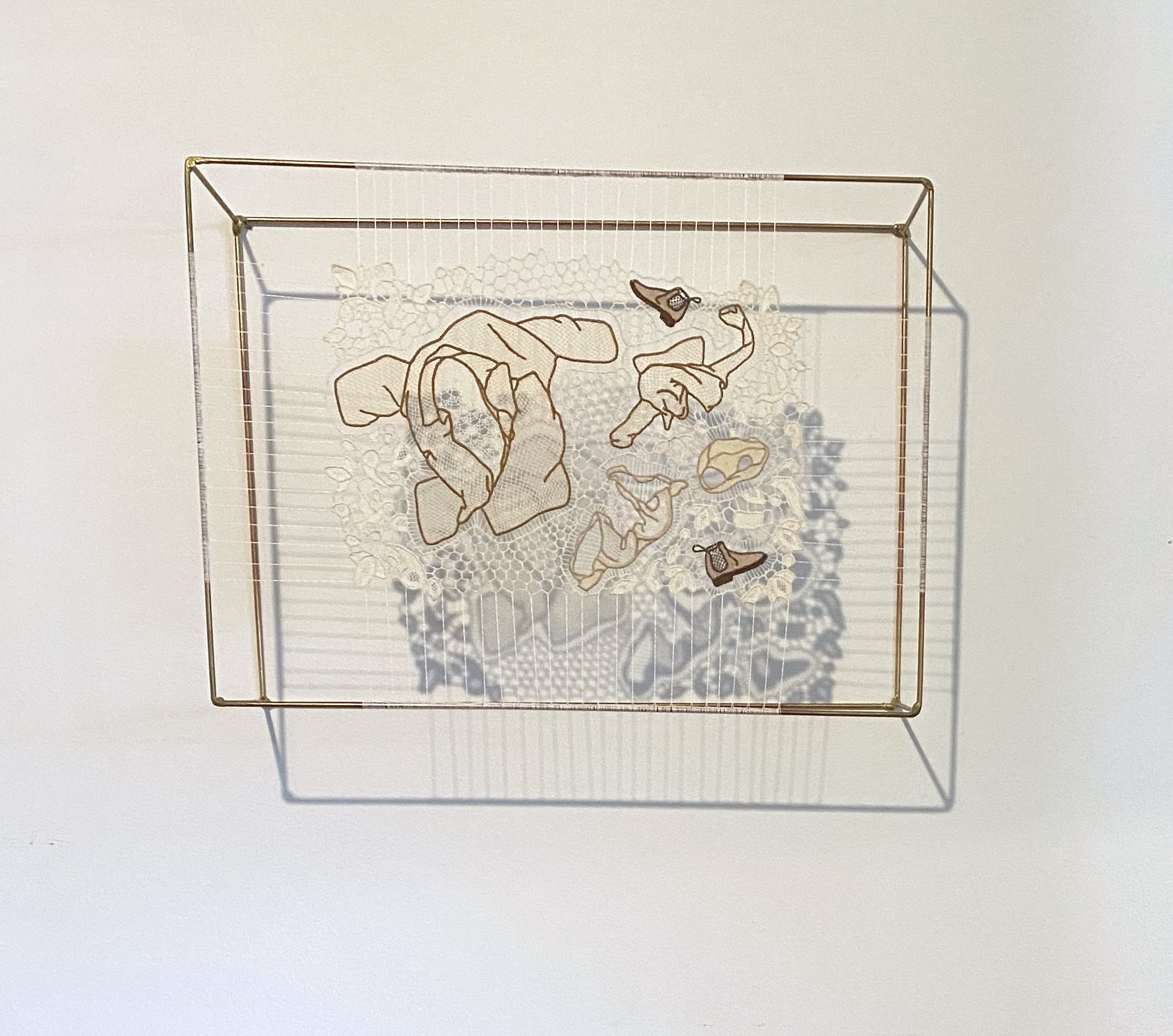

Maggie’s needle lace piece Covid Floor was also made during 2020. The intricate technique of needle lace was once used to portray scenes of historical and religious significance. Here, the eye turns inwards, immortalising the exhaustion and ennui of lockdown – a feeling that for many has never entirely dissipated. (For those already living with chronic illness, the lockdowns may have simply heightened pre-existing isolation.) The miniature form of the artwork also functions as a kind of container for the unmanageable and the precarious. Bachelard writes: “The cleverer I am at miniaturising the world, the better I possess it.” (2)

~

A lot of people turned to craft during the lockdown years. Repetitive actions, tactile processes. Quilting, embroidery, ceramics. Activities to keep the hands busy and define the body’s edges.

After World War I, returned soldiers were taught embroidery to deal with physical and mental trauma. (3)

In 1800, an English woman named Anna Larpent wrote in her journal about using needlework to manage her emotions during a period of grief and worry.

“I always find when my spirits are oppressed and I cannot follow what I read that some regular progressive work occupies my mind best”. (4)

The thing about progression is that you feel you are heading somewhere.

~

I plan an exhibition at my house, to be held in 2021. Artworks that use accumulation, accretion, repeated gesture. Artworks about being sick and exhausted, about fatigue, about anxiety. Being safe inside your house but/and the walls of the house closing in on you. Being in the unstable porous precarious home of your body.

I borrow a book from the library, The gorgeous nothings, a facsimile collection of Emily Dickinson’s ‘envelope poems’. (5) (Dickinson was famously a recluse, so it’s no coincidence that I turned to her work during this time.) The envelope poems were written between 1864-1886, the last years of the poet’s life, during which she rarely left her upstairs bedroom. Dickinson only published a handful of poems in her lifetime. After her death, her sister Lavinia discovered around 1800 of her poems, bound into 40 little booklets and stacked in a drawer.

The image of Dickinson as a solitary hermit, uninfluenced by the wider world, is not a true one. While the poet herself stayed home, her words travelled for her, as she corresponded widely with numerous friends and literary figures. As one writer puts it: “Her famously preserved room was effectively a busy message dispatch centre.” (6) From the enclosed, intimate space of her bedroom Dickinson sent out letters, telegrams and poems of startling expansiveness. The envelopes received in return were flattened and saved, to become surfaces for pencilled fragments and jottings. On the interior flap of one envelope, sliced open like a carefully-flayed skin, Dickinson writes in pencil so light it is barely legible:

“Excuse | Emily and | her Atoms | The North | Star is | of small | fabric but it | implies | much | presides | yet.” (7)

In my library book about the envelope poems, an essay by Dickinson scholar Marta Werner is titled ‘Itineraries of Escape’. (8) An itinerary is a planned route or journey, a travel plan. Werner discusses a number of envelope poems in detail, and their allusions to travel and flight, but never directly employs the evocative title phrase in the body of her essay. I imagine Dickinson in her house, accumulating fragments, gathering together her poems; her entire life a collection of plans for escape. Scraps, dust motes, sparkling like a night sky full of stars.

I borrow the essay title for the exhibition.

I decide to write an essay of my own to accompany the show. This essay will artfully weave together all the exhibition artworks with the loose whirling of ideas, quotations and connections jostling in my brain. The essay will provide a clear shape for this exhibition, define its edges.

The journalist Janet Malcolm likens the writing process to entering a hoarder’s house, piled with accumulated detritus. She says:

Each person who sits down to write faces not a blank page but his own overfilled mind. The problem is to clear out what is in it, to fill huge plastic garbage bags with the confused jumble of things that have accumulated there over the days, months, years of being alive and taking things in through the head and the heart. (9)

Malcolm goes on to describe the anxieties that accost the person faced with this clutter, “the dangers of throwing the wrong things out and keeping the wrong things in”, or throwing out too much, or throwing out everything, unable to stop. She writes: “It may be better not to start.” (10)

~

In the kitchen is an accumulation of orange-yellow dust (Excuse Emily and her Atoms). Cheezels, reduced to their smallest particles, are packed densely into shelves, nooks and crannies.

Anita’s installation is called feelings. In its original form, it was a yellow wall-to-wall carpet, perfectly smooth and sheared at the edges. Here, feelings are crammed into tiny spaces. Anita once made a version of this work with Cheezel dust filling Perspex boxes. They tell me that some of the boxes have since burst open, pushed apart by the pressure of the feelings they held.

An eight-metre collage of sliced Cheezels boxes – titled I got out of bed today – has been reproduced for this exhibition across two pillowcases. Limited edition soft furnishings for the chronically exhausted.

Excuse Emily and her Atoms. My subject matter may be humble, Dickinson seems to be saying, but the North Star – that faithful cosmic guide – is made of the same stuff. All matter is stardust. Cheezel dust.

~

Gemma says that she is finding ways to make art around “long Covid/life fatigue”, and without a designated studio space. Making things in and around the detritus of daily life. She has moved to a Perth suburb named after a small blue lily that was once plentiful in the area; her pinboards are grey to reflect the concrete that now thrives in its place. “I’ve been drawing brick walls (blockages),” she writes to me, “and am also interested in grass and drains at the moment, things from the neighbourhood. Letters and punctuation are still reoccurring themes. Shiny sequin flowers and pressed weeds.” She writes that arranging these things on the pinboards feels “like making a spell”. (11)

Fragments pinned together, some kind of wordless poem, space opening up between objects. The flower is an oh, the pin is an oh, the cut paper is an oh. Atoms, scraps, “small fabric”.

~

During lockdown, Renae lived in a series of homes plagued with black mould. Invisible at first, after heavy rain the mould bloomed and spread across walls and carpets, its spores settling in soft furnishings and clothes and books and craft supplies.

For months Renae was sick with mysterious ailments, constantly fatigued, her breath constricted. Even once she figured out the probable cause, the solution was unclear: the first treatment of an allergy is to remove the allergen, but what do you do when you’re living inside it? When your home is making you sick?

The Old Testament book of Leviticus describes the treatment for a house with what the King James translation calls ‘leprous plague’: mould. This involves removing and replacing the afflicted stones and scraping down the house’s interior walls. Once this is done, and a priest has declared it to be mould-free, the priest enacts the following ritual:

To purify the house he is to take two birds and some cedar wood, scarlet yarn and hyssop. He shall kill one of the birds over fresh water in a clay pot. Then he is to take the cedar wood, the hyssop, the scarlet yarn and the live bird, dip them into the blood of the dead bird and the fresh water, and sprinkle the house seven times. He shall purify the house with the bird’s blood, the fresh water, the live bird, the cedar wood, the hyssop and the scarlet yarn. Then he is to release the live bird in the open fields outside the town. In this way he will make atonement for the house, and it will be clean. (12)

Using a mending technique called Scotch darning, Renae constructed a pair of lungs: one pink, one blackened. Soft rows of looping threads. Painted in a ceramic vessel: a dead bird, a live bird, and a cup containing red yarn, a cedar stick, and a hyssop bough. In this way the house will be cleansed.

(Our landlord tells us that the dark mould that blooms inside the bathroom cupboard is in fact “condensation”.)

~

Ellen’s quilt is made from yellow yitaeri towels, used for scrubbing the body. You slip one onto your hand, rub rub rub, slough off the dead skin cells. In a bathhouse you are scrubbed by a Saeshinsa, a professional scrubber. In the text accompanying this work, Ellen recounts visiting a Korean bathhouse with her grandmother and being scolded: “Eolmana ttaereul anmileotseomyeon ttaega gooksooga daeno” (You really didn’t scrub your body to a point where we can make noodles with your dead skin). In a video, Ellen scrubs repeatedly at her own birthmark: The mark, the link that can’t be erased and never fades 사라지지도 지워지지도 않는 자국, 그 연결 고리. The desire to fully inhabit one’s culture and family of birth, the desire to separate oneself from it. The impossibility of both. The entanglement of identity. Scrub scrub scrub.

Ellen’s text is titled “The heat rises, and there is no silence”. A steamy, sensory overwhelm; an echoing babble engulfing the body.

~

Sophie’s sculpture Stick and Poke conjures the presence of a small child’s body through clothing, encrusted with stickers like garish scabs. “The clothes stand stiff,” writer Tara Heffernan says of this work, “as if encasing a rigid, invisible body—an unyielding little ghost of past trauma.” (13) This work represents the embodied memories of childhood medical procedures, “life-saving but life-altering”, (14) with stickers to reward bravery for each stick and poke. Plastered with smileys, hearts, flowers and bunnies, it’s an excess of breezy positive vibes and get-well-soons; an empty shell of insistent optimism.

Bachelard again: “…an empty shell, like an empty nest, invites daydreams of refuge.” (15)

~

The exhibition is postponed because Melbourne goes into another lockdown, then another and another. Our living spaces are getting smaller, pressing in on us. We are being compacted into tiny spaces. Something has to give.

The exhibition is postponed indefinitely. I slide down into a dark pit. I can’t work. I can’t read. I make a kind of nest on the pull-out couch, the one that is partly propped up with a brick. Each day I drag myself through the morning routine and then lie on the couch, too exhausted to move. When I have the energy, I sit propped up with pillows and stitch tiny pieces of fabric together: an endless patchwork with no purpose except getting through the days. I am tethered to the couch by an invisible leash.

~

In her 1797 diary Anna Larpent describes the soothing process of needlepoint:

the monotony & mechanism like the returning sound of water or any other sensation that marks time calms the spirit by fixing the attention then the glowing colours & shading please the Imagination. (16)

My brain is clogged with sludge. My sewing is regular progressive work, but I don’t know where it’s progressing.

I write in my journal that the couch is “an island where I can’t act on the thoughts that crash on me like waves … sometimes just lapping gently, but always there if I look.”

The returning sound of water.

I write in my journal: It feels like I’m submerged.

~

In the hospital they zap my brain with magnets. It’s a treatment called TMS: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. I sit in a reclining chair, the kind they use at the dentist. The nurse measures my head and draws a dot on it with a whiteboard marker, on the top left. She lines up a metal plate with the dot. “Why is it on the left hand side?” I ask the doctor. “Because that’s where the depression lives,” he says. I picture a small dark furry thing, an eyeless creature with stunted limbs, curled up in my skull cavity just below the dot.

The magnet is switched on. It emits a series of pulses like repeated blows – not painful, but insistent. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak. Pause. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak. Pause. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak.

We do this for twenty minutes every day for twenty days. If I accidentally shift my head while the magnet is pulsing, my right hand twitches uncontrollably. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak.

The monotony and mechanism of these pulses are supposed to interrupt the sad dull animal settled in my brain. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak. For fourteen days I don’t feel any different. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak. On the fifteenth day, something shifts. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak. And continues to shift. Taktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktaktak.

~

I’ve been writing this for three weeks, I’ve been writing this for three years. Sorting through my overfilled mind. Writing out the clutter so I can put it in garbage bags and clear it away.

~

Two days before I am discharged from hospital, we are told that our lease is not being renewed.

We look at sixteen houses that meet our budget. The first fifteen are terrible.

One house is entirely floored with tiny dark-brown square tiles, including the bedrooms. The entire kitchen is slightly bigger than a walk-in pantry.

One house advertises a ‘separate bungalow room’ that turns out to be a former outhouse toilet.

One house includes a ‘bedroom’ with swinging saloon doors, the kind that are open top and bottom, and don’t latch.

One house features a separate single-room bungalow which includes a sink with no taps, and no ceiling lights. Two circular orbs, the kind normally mounted underwater in swimming pools, are fixed to the bungalow’s interior wall like two glowing breasts.

One house consists of two small pre-fab homes pushed together. The floors are modelled after rolling dunes and a bedroom window is jammed up against the wall of the second house, like an eye pressed against a telescope with the eyepiece on. It’s a warren of corridors and dead ends, and smells of mildew.

The sixteenth house is this one. We are relieved beyond belief.

Two weeks after we move into our new house, my skin breaks out in hives. Red itchy welts bloom on my legs and arms and stomach and neck. I anoint myself with creams. I swallow antihistamines and steroids. I get blood tests. I see specialists. They rule out allergies, chemicals, mould. Eventually they kind of throw up their hands and tell me it’s probably my body reacting to stress. Have I experienced any stress lately? The stress has inhabited my body, is leaking out of my body at its porous edges.

I take five antihistamines a day and the hives blessedly vanish; my skin is cleansed and purified. After three months I wean myself off the pills and the hives stay gone.

~

Ruby’s large work, Longing, was made during 2019-20. It’s part of a series made using a caulking-gun and acrylic gap-filler – an industrial material designed to seal up wounds in the house’s leaky skin. Squeezing out beads of gap-filler, pressing each one flat with a finger, Ruby builds up a new surface in layers.

This body of work emerged out of necessity, using materials on hand to fill an absence of making. She writes that she loves “the rhythm that comes with quickly touching each plasticky bead before it dries.” A regular progressive task, “quiet and repetitive”. (17)

Originally from Aoteroa New Zealand, Ruby writes: “While making this series I’ve been thinking about connection to this land that is not mine. The trees in the Australian bush are mesmerising. There is a language in them that I do not know.” (18)

~

The exhibition is postponed because on the other side of the world a nation of people is under violent siege. Bombs crash down like terrible waves, collapsing whole neighbourhoods. This carnage is about who can claim this enclosed piece of land as their home. In that place people beam out videos and photographs and messages and tweets. A volley of desperate pleas for escape are transmitted into our homes. We lie in bed moving our thumbs across glass rectangles, watching videos of dead children dragged from under the rubble of their former bedrooms.

The accumulated weight of rocks. The monotony and mechanism of human brutality.

The exhibition was planned for a Sunday, but now every Sunday tens of thousands of people gather in the city, packing Swanston Street from the library to the train station like a throat filled with words.

This land – both the land being bombed and the land we’re gathering on – is dense with thousands of years of accretions and accumulations taken in through eyes and ears and hearts. How can you begin to make sense of it? What if you throw away the wrong things and keep the wrong things? Is it better not to start?

A hundred thousand people protest one Sunday and not a single media outlet mentions it. The words travel along the throat and out of the mouth into empty air.

Oh oh oh. The wordless cry of the blank page, the overfilled mind. Oh encompasses the inexpressible, the inarticulate, an atom, a universe.

~

An oh is a rock is a stitch is a filled gap is a curl of skin is a sticker is a mould spore is a speck of Cheezel dust.

~

The essay is not a container because none of these things can be contained.

~

I google the exhibition title and find cruises to Norway, on a ship called the Escape.

(1) Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon, 1994), 72.

(2) Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 150.

(3) Erica Prus, “Soldiers embroidering”, Textile Research Centre, accessed 22 Nov 2023, https://www.trc-leiden.nl/trc/index.php/en/blog/1313-soldiers-embroidering.

(4) Anna Larpent, March 1800, M1016/1. Cited in Bridget Long, “‘Regular Progressive Work Occupies My Mind Best’: Needlework as a Source of Entertainment, Consolation and Reflection,” TEXTILE 14, no. 2 (May 3, 2016): 176–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2016.1139385.

(5) Emily Dickinson, Jen Berwin and Marta L. Werner, The gorgeous nothings: Emily Dickinson’s Envelope Poems (New York: Christine Burgin/New Directions, 2013).

(6) Daniel Larkin, “Emily Dickinson was less reclusive than we think”, Hyperallergic, 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/372801/emily-dickinson-was-less-reclusive-than-we-think/

(7) Emily Dickinson, Amherst College Library Digital Collection, A 636/636a, https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/EmilyDickinson/ed0636

(8) Marta Werner, “Itineraries of Escape: Emily Dickinson’s Envelope Poems”, The gorgeous nothings, 199-226

(9) Janet Malcolm, The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, 3rd edition (London: Granta, 2012), 204

(10) Malcolm, The Silent Woman, 205

(11) Gemma Watson, email correspondence with the author, 20 October 2023

(12) Leviticus 14:49-53, New International Version.

(13) Tara Heffernan, “Other Body Knowledge,” Other Body Knowledge: Contending with the Mythic Norm, 2022, https://www.kingsartistrun.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/OBK-digital-catalogue.pdf

(14) As above.

(15) Bachelard, The poetics of space, 107

(16) Anna Larpent, July 1797, M1016/1

(17) Ruby Brown, “Longing”, accessed 22 November 2023, https://www.ruby-brown.com/#/longing-ruby-brown-artist/

(18) As above.